Tired of troubleshooting? Wish that you can pre-empt problems before they occur?

Thanks to Upstream — How to Solve Problems Before They Happen by Dan Heath, we now have a way to do so!

An acclaimed author in social psychology with his brother Chip Heath (read my review of their book The Power of Defining Moments), Dan’s latest volume shed interesting insights on how cities, organisations and individuals can intervene upstream to prevent small issues from snowballing into large crises.

Seasoned with case studies from the worlds of education, crime, natural disasters, to sports and online commerce, Upstream provided lots of food for thought.

Wouldn’t the world be much better if we can eliminate problems before they become full-blown catastrophes? (Case in point — our seemingly relentless Covid-19 global pandemic.)

Let us now look at some of the salient points from the book.

Challenges to Upstream Work

If solving problems before they happen is so important, why don’t more of us do so?

According to Dan, there are three reasons why they do not occur:

- Problem Blindness — I don’t see the problem or its inevitable. This is the failure to consider that problems can be prevented, eg getting injured during sports (“Pro athletes play hard. Injuries are gonna happen.”)

- A Lack of Ownership — That’s not my problem to solve. Often, problems do not get fixed because those who cause it are unable to do so, while those who can do not see it as their responsibility.

- Tunneling — I can’t deal with that right now. When we’re so mired in our current problems and situations that we cannot escape the trees to see the woods.

How do we resolve these challenges?

- To solve problem blindness, we need to shock ourselves to gain awareness of the real extent of the problem, and search for community (ie find others who also feel the same way and compare notes).

- To solve a lack of ownership, the upstream advocate must appreciate that though you did not create the problem — or are responsible for it — it is in your interest to solve it.

- To solve the problem of tunneling, we need to “create urgency” to make an upstream far away problem (eg climate change) downstream and tangible. This is a form of reverse-tunneling, where we simulate conditions that compels people to take action.

Now that we’ve rectified the roadblocks to upstream thinking, we should consider the seven questions that upstream leaders must consider.

#1 How Will You Unite the Right People?

It takes a village to raise a child. And to melt a problem before it snowballs into a disaster.

To do so, consider assembling a team of Avengers (or Justice League if you’re a DC fan!) to tackle the issue from all angles.

Use the right data — not data for inspection but data that helps you to do corrective actions — to help you decide who should be involved. Surround the problem from all sides.

This may involve getting out of your comfort zone and reaching out to other experts to get them involved in your task-force.

#2 How Will You Change the System?

Often, solving upstream problems require systems-wide changes that may be far-reaching. This should be tackled both within your current organisation as well as external parties.

An interesting example came from the Dutch bicycle company VanMoof. They received complaints that many of their bikes were damaged during shipping.

Their solution? They printed images of flat-screen televisions on the sides of their shipping boxes. Couriers were much more careful, and damaged bikes were reduced by 70 percent to 80 percent.

#3 Where Can You Find a Point of Leverage?

This is key, but to do so, you need to get close to the problem.

Eat, live, breathe and sleep like your customer. Spend a day walking in their shoes to identify where possible interventions could be applied.

Note that you should aim to be as holistic as possible, and not just think of immediate cost savings as the goal. Sometimes, long-term system changes are investment heavy, but the potential benefits can far outweigh the costs. (Think of the billions of dollars involved in disasters.)

#4 How Will You Get Early Warning of the Problem?

The Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting incident is a tragic reminder of how failing to identify warning signs can lead to disaster.

Rather than just teach students and teachers how to deal with aggressive shooters, parent Nicole Hockley tried to target the potential shooter’s mental health. Together with other parents in her group, they discovered that there were early-warning signs. Most mass shootings are planned at least six months in advance. Typically, 8 to 10 shooters tell at least one other person of their plans. Many also post their threats on social media.

This led to the group launching a training programme to educate students nationwide on the warning signs of potential killers. These include a fascination with firearms, acting aggressively, extreme feelings of social isolation, and explicit threats of violence.

Like the Sandy Hook case, see if you can look for predictors and sensors. Use these early warning signs to prevent the first domino from falling.

#5 How Will You Know That You’re Succeeding?

Deploy table-top exercises and gamification techniques to anticipate how things may unfurl in the future.

Also, beware of ghost victories which happens when “there is a separation between (a) the way we’re measuring success and (b) the actual results we want to see in the world” — in short, a superficial success that cloaks failure.

This may involve asking the hard questions and digging into the fundamentals. Here are five questions to ask in any pre-gaming exercise:

- “Rising Tides” Test — Imagine that you succeed on short-term measures. What else might explain the success beyond your own efforts, and how do you track them?

- Misalignment Test — If your short-term measures do not reliably predict success on your ultimate mission, what can you do to weed out misalignments as early as possible? What alternate measures may work better?

- Lazy Bureaucrats Test — If someone wants to succeed with the least amount of work, how would they measure the results? Can we then prevent this?

- Defiling-the-mission Test —If you’ve succeeded years from now in achieving your short-term measures, yet failed on your long-term mission, what would be the consequences?

#6 How Will You Avoid Doing Harm?

As a biologist by education, I’m always fascinated by how closely intertwined food chains and food webs are.

The story of Macquarie Island (located halfway between Australia and Antarctica) narrated how unintended consequences can affect the balance of nature. Here’s a summary of what happened:

- Island home to rare species, especially seabirds like the blue petrel, as well as penguins and seals

- 19th and 20th century — hunters and traders sailed to the island to capture penguins and seals

- These humans brought rabbits (as food), mice and rats (accidental stowaways), and cats (to kill the rodents)

- No native predators, hence the introduced species ran wild — “An endless all-you-can-eat buffet”

- By 1960s, conservationists introduced viruses through thousands of fleas as vectors to hopefully kill the rabbits

- After 10 years, the rabbits were immune to the viruses!

- In 1978, the deadly myxoma virus was introduced — rabbits were shot using air rifles with cotton-wool pellets soaked with the virus

- By 1988, over 100,000 rabbits died, reducing total population to under 20,000. However, cats ran out of rabbits to eat and started preying on the rare seabirds!

- Cats were targeted next — by 2000, all cats were eradicated from island

- Rabbit populations started to rebound, as they developed resistance to the virus. Also fewer cats to eat them!

- Desperate conservationists dropped poison bait out of planes to kill the rabbits, rats and mice. Alas, 1,000 native birds were killed too!

- Last onslaught in 2014? Kill animals with poison bait, shoot them, hunt them with dogs, and unleash a new successful virus called Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (through laced carrots)

The entire effort took nearly 50 years. But wait, the island is now plagued by invasive weeds which were held at bay by the thousands of nibbling rabbits…

This is the age-old question of unintended consequences of side-effects. Quoting from the book:

“What if we succeed at our mission — not just the short-term measures but the mission itself — yet cause negative unintended consequences that outweigh the value of our work? What should we be paying attention to that’s offstage from our work?”

To avoid the equivalent of a Macquarie Island fiasco, you need to anticipate second-order effects as far ahead as possible, use data to forecast outcomes, and conduct careful experimentation guided by feedback loops.

#7 Who Will Pay for What Does Not Happen?

OK, so how do we get people to pay for problems that do not happen? This is the age-old wrong pocket problem, where incentives aren’t aligned with the persons who benefit from them.

(A good example would be medical doctors, who are only paid when their patients come to them for treatments and not when they are healthy.)

Here, Dan suggests a capitation model which is used in health care payment systems. In such systems, a doctor or hospital is paid a fixed amount per patient for a prescribed period of time by an insurer or physician association. This incentivises the healthcare professionals to keep their patients as healthy as possible.

For other industries, a subscription approach for maintenance could also work well. My wife and I used this for our air-conditioning maintenance, where our service professional would inspect and clean the filters and compressor regularly (eg once in 6-months). This reduces the likelihood of major interventions needed downstream.

Living an Upstream Life

Towards the end of the book, we learn how we can incorporate these upstream problem solving principles in our daily lives.

There are three ways to do so.

#1 Be Impatient for Action But Patient for Outcomes

Downstream work is narrow and fast. Upstream work is broad and slow.

To make your upstream interventions work, you need to slow edge your way towards success. Think of continuous improvement (Kaizen) rather than radical overhauls.

#2 Macro Starts with Micro

Familiarize yourself with the details. Go up close (and personal) with each problem case.

Seek individuals who not only can see the big picture, but are familiar with the nitty gritty.

#3 Favour Scoreboard over Pills

Don’t try to look for a silver bullet. Instead, use empirical data and experimentation to slowly inch your way forward.

Conclusion

Being continually online, it is easy for us to get mired in the weeds. Often, we become too obsessed with solving immediate problems to think about what caused them in the first place. The words “troubleshooting” and “debugging” are testimony to this approach.

Thanks to Upstream, we now have a way to examine each problem from a higher vantage point, and to prevent them from happening in the first place. This helps us to minimise painful downstream solutions while (hopefully) improving our performance in every aspect of work, and life.

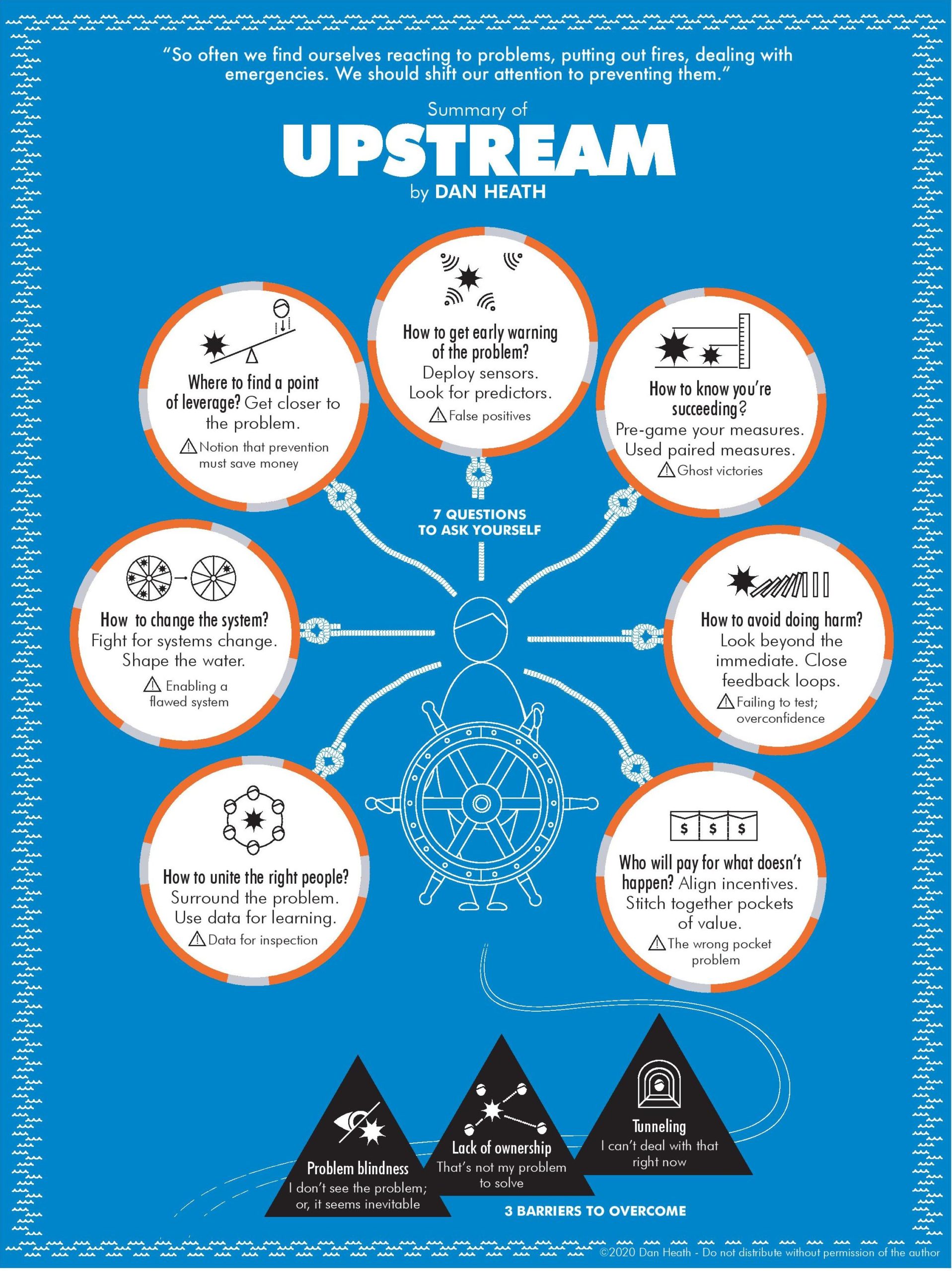

Do register as a member of the Heath Brother’s website to download a free PDF (like the one below) as well as lots of other valuable resources!

The knowledge is helpful.