Image courtesy of Gapminder Tools

Do you know that many of us systematically get our facts wrong? Or that a chimpanzee randomly answering questions may perform better than teachers, doctors, professors and even Nobel Laureates?

That is the premise behind Factfulness: 10 Reasons We’re Wrong About the World, a delightful book by public health professor Hans Rosling (and founder of Gapminder), with co-authors Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund.

Famed for his jaw-dropping statistics on numerous TED Talks (see below), Hans Rosling was a tireless advocate for using facts to correct ignorance, prejudice, and errors in thinking about how the world works.

(Sadly, he passed away in 2017 from incurable pancreatic cancer, but his legacy continues with his son and daughter-in-law.)

Divided into sections addressing the 10 most common errors in thinking about the world, Factfulness convinces us that the world isn’t as bad as we make it out to be.

Rather than follow an overdramatic worldview (often fanned by the media), we should adopt a fact-based worldview—one that is informed by logic, rational thinking and data.

For instance, do you know that over 80 percent of the world’s children under one-year-old has been vaccinated against some disease? Or that only 11 percent of the world’s population do not get enough food to meet their daily needs?

Let’s look at each of these “thinking illusions” in detail.

#1 The Gap Instinct

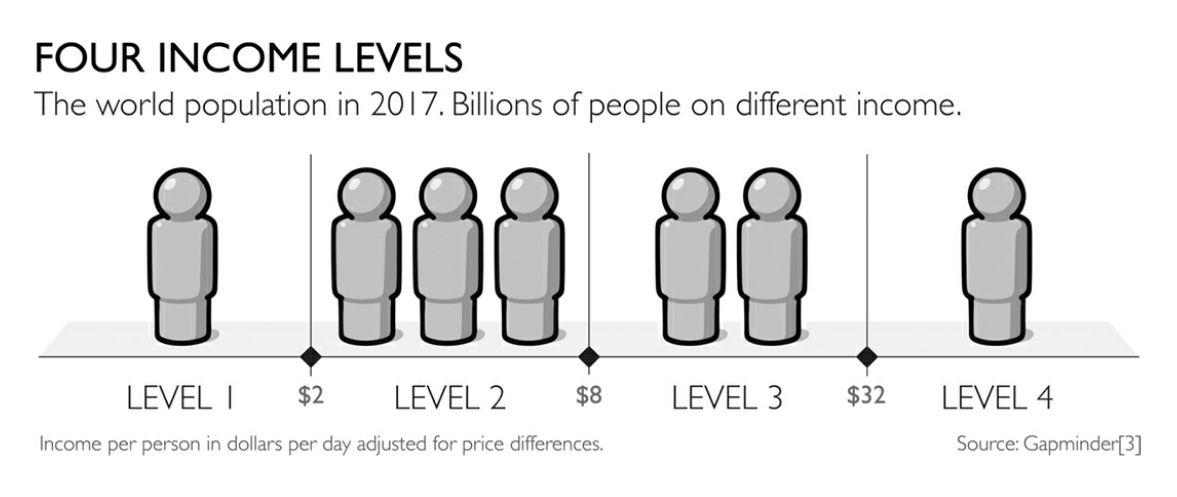

Contrary to popular belief, the world isn’t divided into two: the “haves” and the “have nots.”

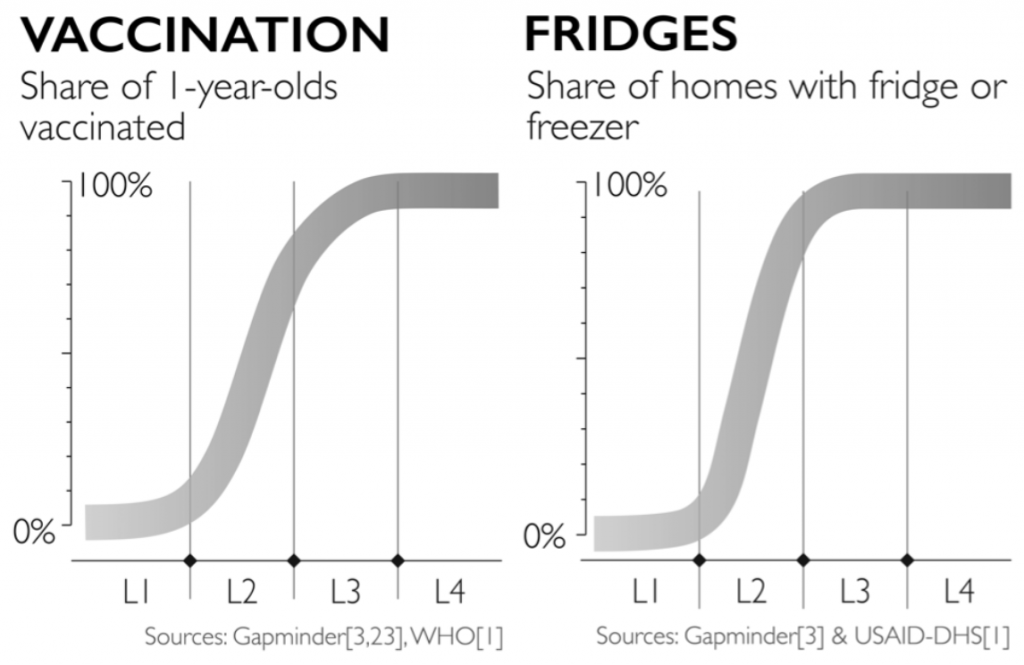

On the contrary, many of the people in the “developing” countries are pretty similar to those in “developed” countries—once they’re reached a certain level of income. According to Rosling, there are four levels of income in the world as shown by the chart below. Each level roughly has the same standards of living, regardless of the countries that they come from.

Courtesy of Gapminder

How to Overcome Our Gap Instinct

- Beware of comparing averages — look for the spreads to see where there are overlaps instead

- Beware of comparing extremes — don’t be swayed by the ones at the top or at the bottom, as the majority are in the middle

- Avoid the “view from up here” vantage point — go down to each level to look at the details so that your view isn’t distorted

#2 The Negativity Instinct

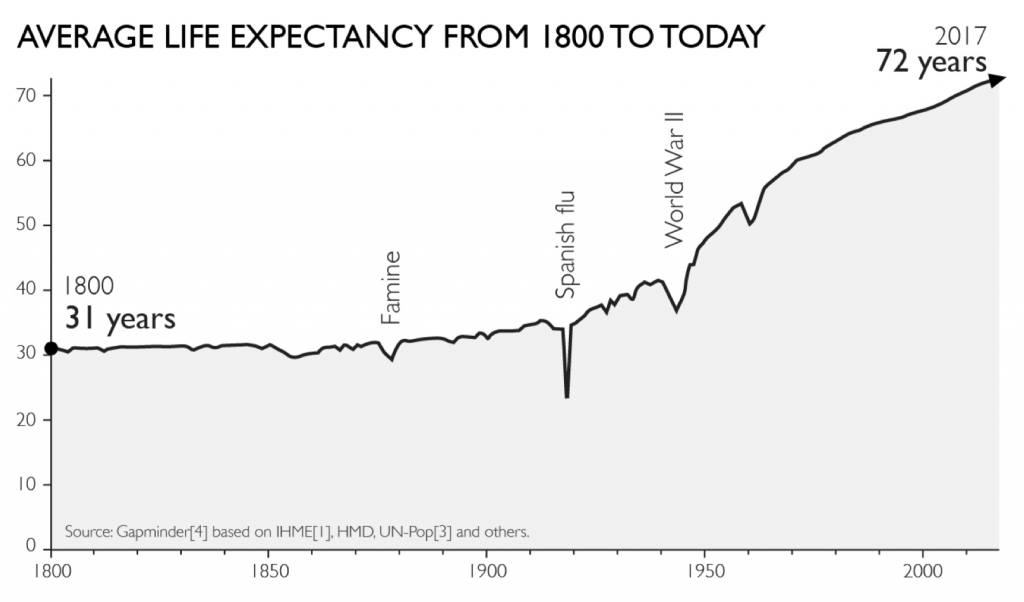

Many of us have the view that “the world is getting worse” which could be painted by dramatic news about the worrying state of the world today. We also tend to let our feelings override our thinking.

Contrary to popular belief, only 9 percent of the world is in extreme poverty state today. Also, the average life expectancy of the world today is 72 years!

Courtesy of Gapminder

From deaths from plane crashes and shark deaths, to global literacy and poverty, much of our narrative in the world is wrong. This is because of our selective memory, where we imagine bad events to be much more prevalent than they truly are.

How to Overcome Our Negativity Instinct

- Distinguish between a level (eg bad) from a direction of change (eg better). Things can be both better and bad.

- Good news isn’t reported. Hence, bad news gets disproportionate coverage (read this for more context).

- Gradual improvements do not get reported. Hence, you are less likely to know that they are happening.

- More news does not equate with more suffering. Its just the way the media works!

- Beware of rosy pasts — people tend to glorify their early experiences

#3 The Straight Line Instinct

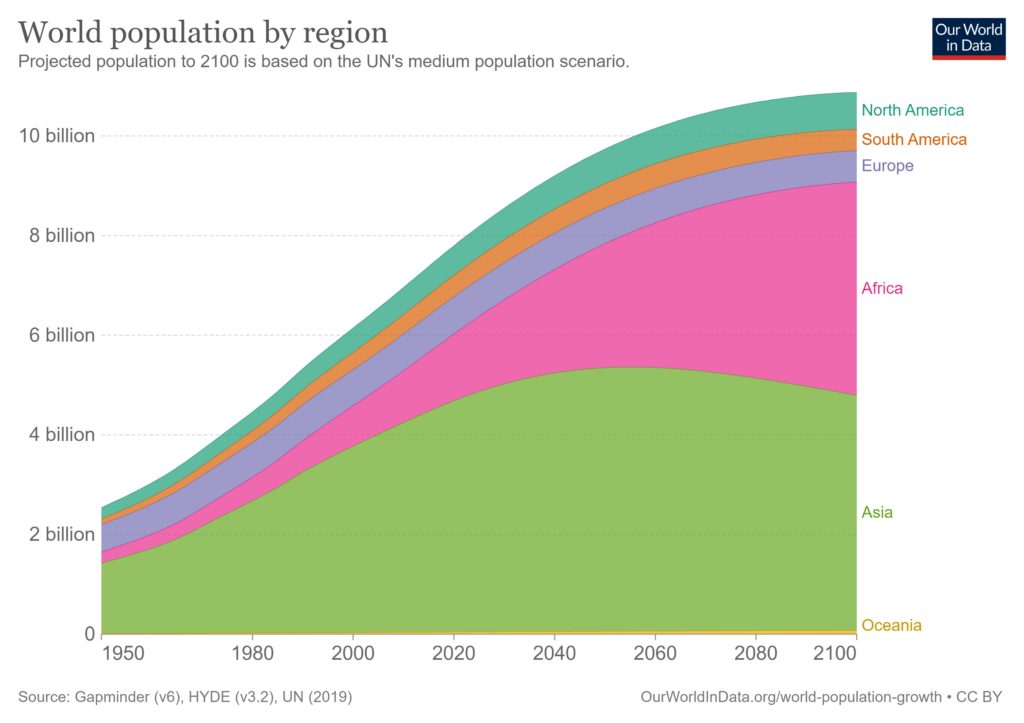

We tend to extrapolate past experiences with a straight line going ahead (eg the world’s population will explode), but this isn’t always the case. For example, in the world population, the growth rate is expected to slow down and flatten, according to UN’s forecast.

There are actually many different types of curves when it comes to both natural and manmade phenomena like humps, S-bends, doubling lines etc.

Courtesy of Gapminder

How to Address Our Straight Line Instinct

Simple. Don’t assume straight lines. Instead, consider how other ways in which populations grow (or decline) or go through cycles like S-bends, slides, humps, or doubling lines.

#4 The Fear Instinct

The fear of certain items is hardwired into our brains. They may include physical harm, captivity, or contaminations.

While these fears may still apply for people living on Levels 1, 2 and 3, they hardly matter to the rest of the world on Level 4.

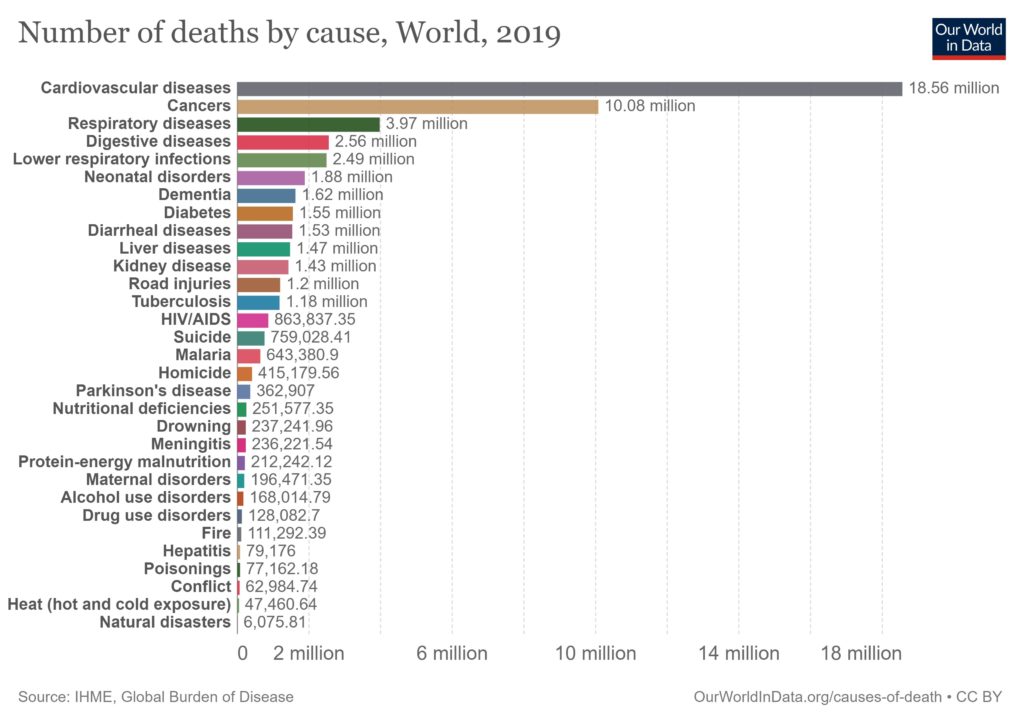

From natural disasters and wars, to plane crashes and terrorist incidents, frightening incidents get our attention. However, these are often not necessarily the most risky — we’re much more likely to die from a heart attack or a car crash than a terrorist bombing incident!

Courtesy of Our World in Data

How to Overcome Our Fear Instinct

Rosling advice here is to calculate the risks:

- Consider that the world often seems scarier than it is because of our attention filter as well as what the media chooses to amplify

- Risk = danger x exposure. Hence, it isn’t how dangerous it is per se, but also how exposed you are to these dangers.

- Keep calm before you carry on. Don’t make decisions until your panic has subsided.

#5 The Size Instinct

All of us are guilty of getting things out of proportion.

We systematically underestimate certain numbers: the proportion of children vaccinated in the world (correct answer is 88 percent); the proportion of people with electricity (85 percent); and proportion of girls in primary school (90 percent).

At the same time, we overestimate certain numbers: the proportion of immigrants in countries for instance.

How to Control Our Size Instinct

- Compare numbers against each other. Single numbers on their own may look big, and make you suspicious.

- Adopt the 80/20 rule: Look at the few largest items in a long list and deal with those first. They are most likely to be the most important causes you should focus on.

- Divide to get rates. Rates may be more meaningful than just pure amounts, especially when we compare against different-sized groups.

#6 The Generalization Instinct

Admit it, you’re probably prejudiced or bigoted in some way or other. Ditto for me.

Everybody automatically categorizes and generalizes all the time. It is necessary for our survival, and helps us to make sense of the world.

However, generalization may make us think of “us” and “them” as all the same when the truth isn’t so.

A good way to dispel this is to do what Dollar Street has done—photos are used to dispel myths and stereotypes of the world. Have a look at how similar beds are around the world based on certain levels of income.

How to Manage Your Generalization Instinct

To prevent yourself from applying the wrong categories and over-generalizing, consider these:

- Find differences within each group of people, especially when the groups are large. Split them into smaller, more precise categories.

- Look for similarities across different groups.

- Also, look for differences across groups. For example, not all people living on Level 4 have the same priorities.

- Avoid just thinking in terms of majority — 51 percent is vastly different from 99 percent

- Be careful of vivid and overdramatic examples. These are the extremes — the exception rather than the rule.

- Assume people are not stupid — if something strange or peculiar happens, be curious and humble enough to find out why this is so

#7 The Destiny Instinct

What is the destiny instinct? Well, it is the idea that innate characteristics determine the destinies of people, countries, religions, or cultures.

In layman language, we think that things will always be the same way and will never change. That people will always behave in certain ways because of who they are.

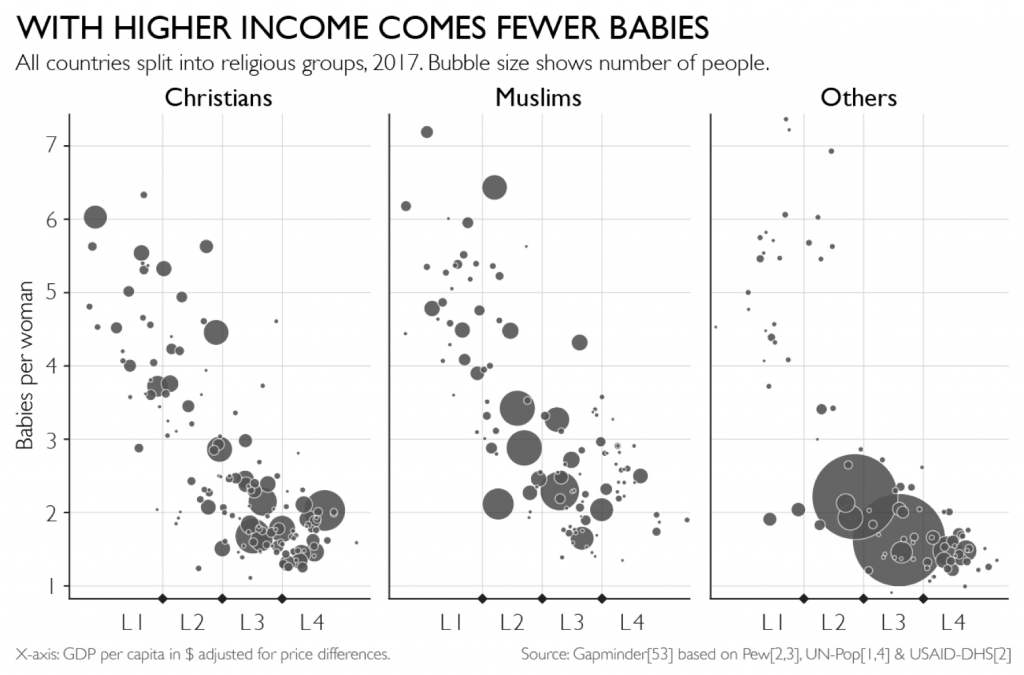

Have a look at this chart from Gapminder, which shows how having higher income leads to fewer babies — regardless of religion or beliefs!

How to Overcome Our Destiny Instinct

To ensure that we do not stereotype others, consider the change may happen slowly — slow change is still change:

- Take note of small, incremental and gradual improvements – this may translate to huge changes over decades

- Update our knowledge of technology, countries, societies, cultures and religions. Africa isn’t just a single homogenous mass of people, for example!

- Talk to your grandparents and notice how different their perspectives are from yours. This shows how values can change wiht time.

- Collect examples of cultural change to determine how yesterday’s culture has changed to today, and will continue to change in the future.

#8 The Single Perspective Instinct

When your only tool is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail!

The single perspective instinct is this preference for us to go for simple ideas. We love easy solutions — like an attention-grabbing big idea that can explain the whole world with a single cause.

Unfortunately, this often isn’t true. For instance, better medicines may not be the best way to improve longevity amongst poorer communities, but basic hygiene, availability of water, and education may work better.

How to Circumvent Your Single Perspective Instinct

Get an entire toolbox of solutions, and not just a hammer!

- Test any idea with experiments and data — find people who disagree with you and get them to test your ideas

- Don’t pretend to be an expert outside your field. Similarly, be mindful of the limits of expertise of others.

- If you are good with a tool, you may use it too often. Remember that no one tool is good for everything.

- Don’t just look at numbers alone — go deeper to understand the context behind those numbers.

- Beware of simple and elegant ideas and solutions. Embrace complexity and combine ideas to solve problems on a case-by-case basis.

#9 The Blame Instinct

This is quite self-explanatory — we’re always looking for a scapegoat! We’re always looking for a clear, simple reason why something bad happened.

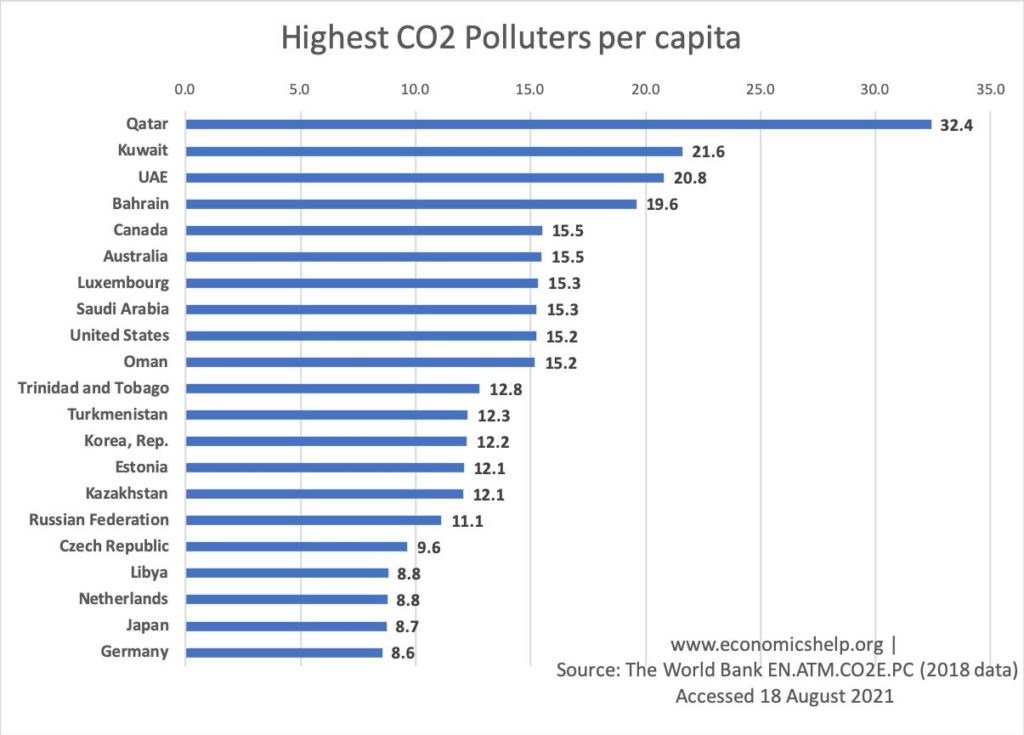

When we do so, our blame instinct results in us attributing more power and influence to individuals than they truly deserve. For example, some in developed countries have blamed India and China for climate change, but look at this chart to show the real culprits.

Courtesy of Economics Help

On the contrary, we should look at entire systems (eg institutions or technology), rather than human all-powerful leaders as the key driver of both good and bad changes.

How to Overcome Our Blame Instinct

Resist finding a scapegoat. Instead, consider looking for causes rather than villains. Find the multiple interacting causes or systems that may cause a situation.

Also, look for inter-connecting systems whenever something good happens, rather than heroes. Ask if the outcome might happen anyway even if the individual did nothing.

#10 The Urgency Instinct

“Its now or never!” sings Elvis Presley, but should we really decide right now in all things?

Sometimes, the urgency instinct makes us do things that are at the forefront of our minds. However, it may lead us astray when we’re faced with more abstract and complex problems.

How to Stop the Urgency Instinct

When a decision feels urgent and immediate, do the following:

- Take a deep breath. Don’t just act, but ask for more time and information.

- Get into the data. However, ensure that the data is relevant and accurate — only those are useful.

- Beware of fortune-tellers and soothsayers. Most predictions are the future are uncertain and oftentimes wrong! Get the full range of scenarios — best, worst and likely.

- Be careful of drastic “massive” actions. Instead consider if these may have any side effects. Take step-by-step practical approaches.

Conclusion — a Thought Provoking Tome

Backed by research and rigorous studies, Factfulness is easily one of my favourite books of all time.

I loved how it uses numerous charming anecdotes to convey its points — storytelling has always been one of the best ways to get a message across.

While many of Professor Rosling’s fans felt sad of his untimely passing, his legacy is one that we should all be mindful of.

Go get a copy of the book.

PS — Try the Gapminder Worldview test to see how you fare. The results are likely to surprise you!